- CARLA Tech Wiki

- LT4 Technology Use Survey

- Tech Integration Modules

- Other Tech-Related CARLA Projects

- CARLA Summer Institutes

- CARLA Bibliography

Brain-based Multimedia: Readings

First, we need to do a little review of how the brain works, some background for the principles we'll show you in the Examples. This module is based on a presentation given a number of times, so you will see slides with descriptive text under many of them.

Click each numbered tab in order to navigate through the content.

Psych 101: Review of Terms

Cognitive Load Theory (see Chipperfield, 2004, for a good illustration) speaks to the task load imposed on our brains while we are learning, but there are a number of steps involved. Prior knowledge is what our students come in with before we start teaching. Prior knowledge should be activated so the student has schema (or chunks of related information) ready to accept new information into it. Prior knowledge can be activated by discussion of a problem related to the content, asking and answering questions about the content, or presentation of an advance organizer that relates the new content to something already known. Sometimes the teacher will need to do some teaching in advance to compensate for students' lack of prior knowledge. It is also important to avoid activating inappropriate prior knowledge, as this will detract from learning. For example, in a lesson about how lightning is formed, photographs of burned roofs or exploded power generators do not bring up the appropriate schema for linking to information about how lightning is formed (Clark, 2003).

Working memory is where all the mental processing happens. Miller (1956) did work that effectively showed that we can only hold 7 ± 2 bits of information in our working memory at one time. The complexity of the task, how many bits and how many processes we have to hold in our memory at one time, will determine if our memory can take it all in and keep it until the end of the task. It is important to form schema (related bits of information) as they combine together and form only one bit. For example, if someone gives you a 10-digit phone number, it is hard to remember them all from putting down the phone until you get to the paper and pen to write them down. However, if the area code is familiar (800, or the your local calling area), the working memory doesn't need to remember all 3 of those digits, just the chunk. Chunking is helped by practice, leading to "automaticity" which is another way of chunking, only this time a process.

Reference

Miller, G. A. (1956). The magical number seven, plus or minus two: Some limits on our capacity for processing information. The Psychological Review, 63, pp. 81-97. Retrieved August 12, 2010, from http://www.musanim.com/miller1956/

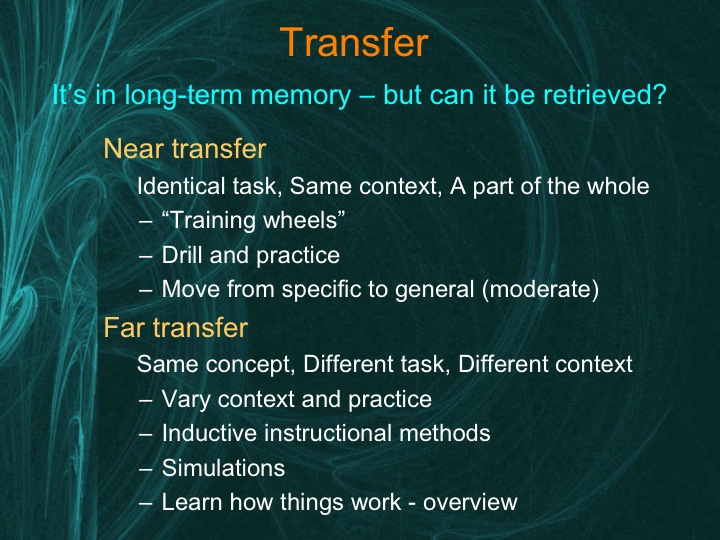

In working memory, one of the keys to learning is active processing. If the information is actively processed, it gets stored into long-term memory which is basically unlimited. Once the information is in long-term memory, however, it is also important to be able to get it out again. Transfer happens when that information in long-term memory can actually be retrieved and applied to new contexts.

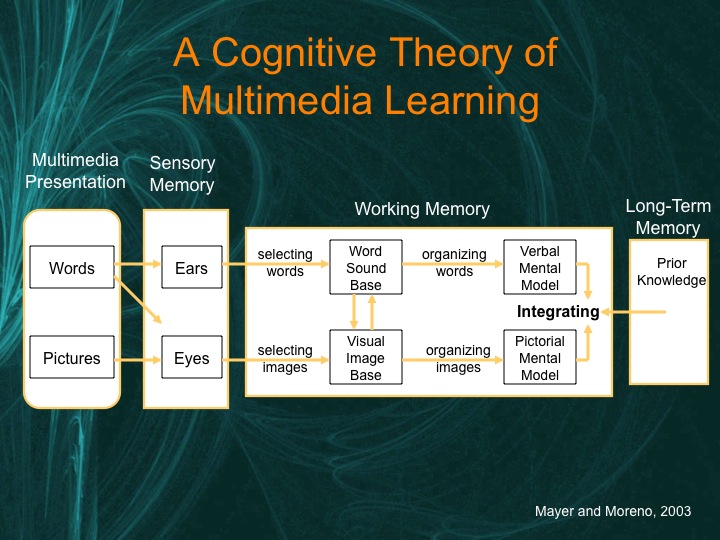

Mayer and Moreno (2003) have developed a theory based on cognitive load theory: the Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning. During presentation of information, we can take in information in two modes: a visual mode (through the eyes), and an auditory mode (through the ears). Text can come through eyes or ears depending on whether it is visual or auditory. Once in the working memory, we start choosing and selecting words and images we deem important and then start organizing them. With active processing, we form mental models and which are hopefully integrated with each other as well as any prior knowledge we may bring to the learning. This dual processing of both visual and auditory information is much more efficient for learning than just one mode at a time.