Requests: Research Notes

Request Realization across languages (Australian/American/British English, Canadian French), Danish, German, Hebrew, and Russian) has been analyzed through the Cross-Cultural Speech Act Realization Project (CCSARP) (Blum-Kulka et al., 1989). The project aimed at investigating request variations across languages (cross-cultural variation), the effect of social variables (sociopragmatic variation), and similarities and differences between native and non-native speaker performance of requests (interlanguage variation). The vast majority of research findings cited below come from the results of this project.

Request Strategies Across Languages

Distribution of main request strategy types in Australian English, Canadian French, Hebrew, and Argentinean Spanish

Request Strategy

Australian English

Canadian French

Hebrew

Argentinean Spanish

Direct

10%

24%

33%

49%

Conventionally Indirect

82%

69%

59%

58%

Nonconventionally Indirect (hint)

8%

7%

8%

2%

While the overall distribution along the scale of indirectness follows similar patterns in all languages, the specific proportions in the choices between the more direct and less direct strategies were found to be culture-specific. Choice of politeness strategies is influenced by both situational and cultural factors which interact with each other.

Proper request expressions are often preceded by prerequests that are face-saving for both interlocutors. Prerequests check feasibility of compliance and overcome possible grounds for refusal. For example, by first asking "Are you free tonight?" the speaker might try to check physical availability of the interlocutor. Since no actual request has been issued, a negative answer at this preliminary stage is face-saving. Speakers can also back out of admitting a requestive intent and the hearers can avoid a requestive interpretation of the prerequest.

Sometimes the prerequest may also function as an indirect request and can be an effective strategy to achieve the speaker’s goal. In response to "Are you free tonight?" the interlocutor might offer help, "Do you need help with your paper?" In this case, the speaker spares the need for an explicit request and again saves face.

Nine sub-levels of strategy types (scale of indirectness)

Direct Strategies

1. Mood derivable (The grammatical mood of the verb in the utterance marks its illocutionary force as a request.)

Leave me alone.

Clean up this mess, please.2. Explicit performatives (The illocutionary force of the utterance is explicitly named by the speakers.)

I’m asking you to clean up the kitchen.

I’m asking you not to park the car here.3. Hedged performatives (Utterances embedding the naming of the illocutionary force.)

I’d like to ask you to clean the kitchen.

I’d like you to give your lecture a week earlier.4. Obligation statements (The illocutionary point is directly derivable from the semantic meaning of the locution.)

You’ll have to clean up the kitchen.

Ma’am, you’ll have to move your car.5. Want statements (The utterance expresses the speaker’s intentions, desire or feeling vis á vis the fact that the hear do X.)

I really wish you’d clean up the kitchen.

I really wish you’d stop bothering me.

Conventionally indirect strategies

6. Suggestory formulae (The sentence contains a suggestion to X.)

How about cleaning up?

Why don’t you get lost?

So, why don’t you come and clean up the mess you made last night?7. Query preparatory (The utterance contains reference to preparatory conditions, such as ability or willingness, the possibility of the act being performed, as conventionalized in any specific language.)

Could you clean up the kitchen, please?

Would you mind moving your car, please?

Non-conventionally indirect strategies (hints)

8. Strong hints (The utterances contains partial reference to object or to elements needed for the implementation of the act, directly pragmatically implying the act)

You have left the kitchen in a right mess.

9. Mild hints (Utterances that make no reference to the request proper or any of its elements but are interpretable through the context as requests, indirectly pragmatically implying the act)

I’m a nun (in response to a persistent hassler).

These subcategories of conventional indirectness vary across languages in conventions of form. In Australian English, the most frequently employed strategies were found to be "can/could you ~," "will/would you ~," and "would you mind ~." In Hebrew, "can you ~," "possibility (ef_ar + infinitive)," and willingness/readiness (muxan + infinitive) seem to be most commonly used. See below for distribution of substrategies of conventional indirectness in four languages. However, the substrategies are probably used in varying proportions in different situations. Most strategies are limited by language and situation except for ability questions that are found to be used by speakers in all languages and all situations.

Rank-ordered distribution of substrategies of conventional indirectness in Australian English, Canadian French, Hebrew, and Argentinean Spanish

Australian English

Canadian French

Hebrew

Argentinean Spanish

1

can/could

67%

can/could

69%

can

41%

can/could

69%

2

will/would

18%

want

11%

possibility

33%

prediction

15%

3

would you mind

11%

possibility

10%

willingness/readiness

18%

future + politeness formula

8%

4

possibility

2%

prediction

5%

perhaps

7%

would you mind

6%

5

how about

1%

would you mind

3%

do you mind

1%

why don't you

3%

6

why don't you

1%

future + politeness formula

3%

Request Perspectives

Distribution of perspectives in requests in Australian English, Hebrew, Canadian French, and Argentinean Spanish

Hearer-oriented

Speaker-oriented

Inclusive

Impersonal

Australian English

62%

33%

2%

3%

Hebrew

55%

14%

1%

30%

Canadian French

70%

19%

6%

5%

Argentinean Spanish

97%

1%

2%

Internal and External Modifications

Internal and external modifications are important mitigating devices to minimize the imposition on the recipient of the request. Internal modification occurs in the head act often in the form of words or phrases, and consists of downgraders and upgraders. External modification, referred to as "supportive moves," takes place before or after the head act.

Internal Modifications (Head Act)

Downgraders

Syntactic downgraders

- Interrogative (Could you do the cleaning up?)

- >Negation (Look, excuse me. I wonder if you wouldn’t mind dropping me home?)

- Past Tense (I wanted to ask for a postponement.)

- Embedded ‘if’ clause (I would appreciate it if you left me alone.)

Lexical/phrasal downgraders

- Consultative devices (The speaker seeks to involve the hearer and bids for his/her cooperation.)

Do you think I could borrow your lecture notes from yesterday?

- Understaters (The speaker minimizes the required action or object)

Could you tidy up a bit before I start?

- Hedges (The speaker avoids specification regarding the request.)

It would really help if you did something about the kitchen.

- Downtoner (The speaker modulates the impact of the request by signaling the possibility of non-compliance.)

Will you be able to perhaps drive me?

- Politeness devise

Can I use your pen for a minute, please?

Upgraders

Intensifiers (The speaker over-represents the reality.)

Clean up this mess, it’s disgusting.

Expletives (The speaker explicitly expresses negative emotional attitudes.)

You still haven’t cleaned up that bloody mess!

External Modifications (Supportive Moves)

While internal modification in the head act may mitigate or aggravate the request, supportive moves affect the context in which they are embedded, and thus indirectly modify the illocutionary force of the request.

Types of External Modifications

Checking on availability (The speaker checks if the precondition necessary for compliance holds true.)

Are you going in the direction of the town? And if so, is it possible to join you?

Getting a precommitment (The speaker attempts to obtain a precommital.)

Will you do me a favor? Could you perhaps lend e your notes for a few days?

Sweetener (By expressing exaggerated appreciation of the requestee’s ability to comply with the request, the speaker lowers the imposition involved.)

You have the most beautiful handwriting I’ve ever seen! Would it be possible to borrow your notes for a few days?

Disarmer (The speaker indicates awareness of a potential offense and thereby possible refusal.)

Excuse me, I hope you don’t think I’m being forward, but is there any chance of a lift home?

Cost minimizer (The speaker indicates consideration of the imposition to the requestee involved in compliance with the request.)

Pardon me, but could you give a lift, if you’re going my way, as I just missed the bus and there isn’t another one for an hour.

Non-conventionally Indirect Strategies (Hints)

Requestive hints in Canadian French, Australian English, and Israeli Hebrew can be categorized into the following substrategies on the two scales: propositional and illocutionary scales. On these scales, (a) is relatively transparent while (c) is relatively opaque.

The Propositional Scale

(a) Reference to the requested act (The speaker explicitly refers to the act.)

I haven’t got the time to clean up the kitchen.

(b) Reference to the hearer’s involvement (The speaker refers indirectly to the hearer’s responsibility but does not name the requested act.)

You’ve left the kitchen in a mess.

(c) Reference to related components (The speaker refers to some object related to the requested act.)

The kitchen is in a mess.

The Illocutionary Scale

(a) Questioning hearer’s commitment (The speaker "checks" whether the hearer feels committed to carry out the intended request.)

Are you going to give us a hand?

Are you going to do something for me?(b) Questioning feasibility (The speaker indirectly or partially asks as to the feasibility of the requested act.)

Do you have a car?

Are you going directly home?

Have you got your notes with you?(c) Stating potential grounders (The speaker presents the reason for the potential request.)

I’ve just missed my bus and I live near your place.

(d) Zero (The speaker makes no reference to any requestive components.)

Attention, Mademoiselle!

(e) Various combination of substrategies above

Distribution of Substrategies of Hints (Blum-Kulka et al., 1989)

Among Australian English, Canadian French, and Israeli Hebrew, there is a common tendency to use the most opaque illocutionary hit substrategies: stating potential grounders, alone or in combination with another substrategy, questioning feasibility. While English is found to prefer high opacity (81%), French and Hebrew are less so (55%, 51% respectively).

Consequences and Characteristics of Hints (Blum-Kulka et al., 1989)

The use of requestive hints may have the following consequences:

(a) The addressee may fail to recognize the speaker’s intentions, although the addressee may still voluntarily carry out the implied requestive act.

(b) The addressee may recognize the speaker’s intention but pretend to understand the literal utterance meaning only, ignoring to respond to the implied request.

(c) The speaker may deny any requestive intentions.

Considering these potential consequences and tendency for high opacity, requestive hints may be seen as having a high deniability potential. Hints are rarely used request strategies, and this may be due to the low efficiency in getting the requested act performed.

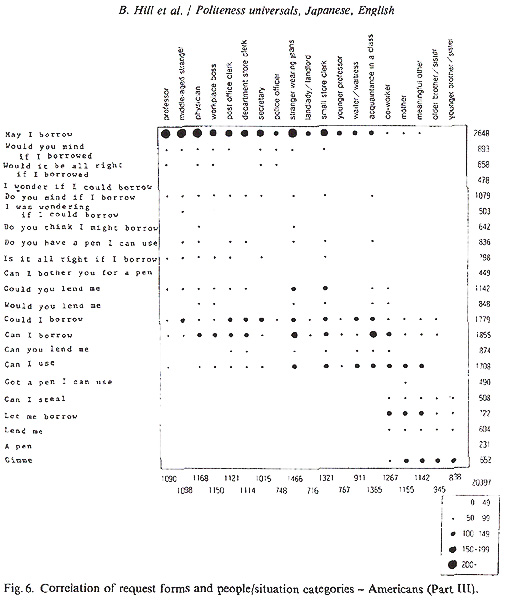

American Requests

Request forms and interlocutor categories in American English (Hill, et al., 1986)

Japanese Requests

Request strategy types and examples (Kashiwazaki, 1993)

Making direct request

kagiwo kashite kudasai ‘Please lend me the key’Asking for cooperation

kagiwo kashite itadakemasuka ‘Would you lend me the key’Explaining speaker’s situation

kagiwo motte naindesuga ‘I don’t have the key’Stating speaker’s purpose

kagiwo karitainndesuga ‘I’d like to borrow the key’Inquiring about hearer’s situation

kagiwo omochi desuka ‘Do you have the key’Inquiring about general situation

heya aitemasuka ‘Is the room unlocked’Asking for permission

kagiwo karitemo iidesuka ‘Would it be okay if I borrowed the key’Stating topic only

kagiwa(wo) ‘(About) the key’Inquiring about speaker’s possibility

kagiwo karirare masuka ‘Could I borrow the key’Direct declaration

kagiwo karimasu ‘I’ll borrow the key’

Request strategy types and syntactic structures (Mizuno, 1996b)

To view a copy of Mizuno's strategy types and syntactic structures graph please select the appropriate format from the list of choices below:

- PDF (requires Acrobat Reader)

- Microsoft Word (28k)

References

Blum-Kulka, S., House, J., & Kasper, G. (1989). Cross-cultural Pragmatics: Requests and Apologies. Norwood, NJ: Alblex Publishing Corporation.

Hill, B., Ide, S., Ikuta, S., Kawasaki, A., & Ogino, T. (1986). Universals of linguistic politeness: Quantitative Evidence from Japanese and American English. Journal of Pragmatics, 10, 347-371.

Kashiwazaki, H. (1993). Hanashikake koudouno danwabunseki: Irai youkyuu hyougenwo cyuushinni [Discourse analysis of requests with phatic communication]. Nihongo Kyouiku [Journal of Japanese Language Teaching], 79, 53-63.

Mizuno, K. (1996b). ‘Irai’ no gengo koudouniokeru cyukangengo goyouron (2): Directness to perspective no kantenkara [Interlanguage pragmatics in the speech act of request: Directness and perspectives]. Gengobunka Ronsyu 18(1), 57-71.