Japanese Requests

Request Segments

Just as in other languages or language varieties found in the Cross-Cultural Study of Speech Act Realization Patterns (CCSARP) project (Blum-Kulka, House, & Kasper, 1989), Japanese requests consist of:

Head Act - the nucleus of the speech act or the part that functions to realize the act independently

kashite itadake masende syouka? ‘would you mind lending it to me?’Supportive Move - modifications that precede or follow the Head Act and affect the context in which the actual act is embedded.

Moshi otemotoni arimashitara ‘if you have it at hand’

Head Act

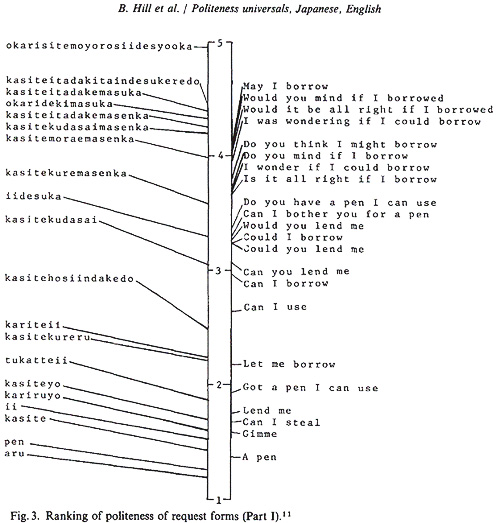

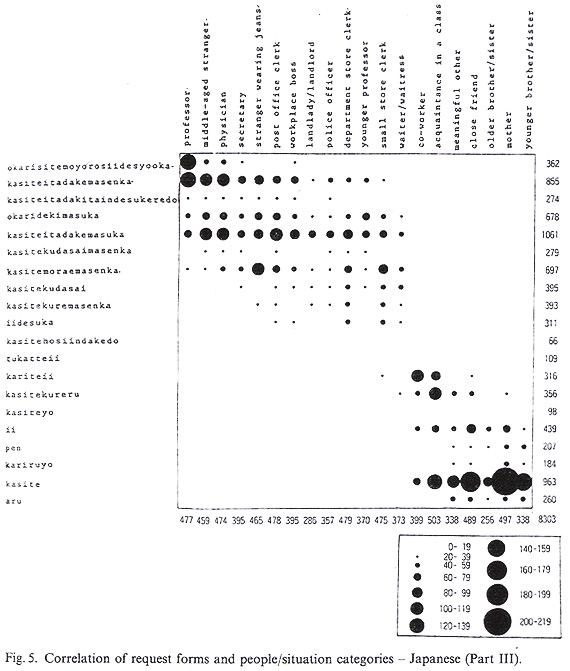

Below is the relative ranking of politeness of request forms both in Japanese and English (Hill et al., 1986):

1 – when being least polite/uninhibited

5 – when being most polite/careful of your speech

Chart form Hill

et al. (1986), p. 355.

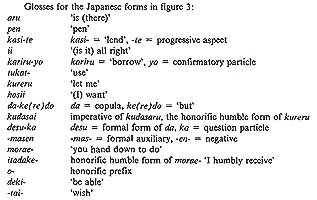

Request forms and interlocutor categories in Japanese

Chart form Hill

et al. (1986), p. 357.

[ Other categorizations of request strategy types... ]

Supportive Moves

Some supportive moves precede the actual request (Head Act) and imply that the request is on its way and thus mentally prepare the recipient of the request, and/or provide explanation or justification of the upcoming request. Other supportive moves follow the Head Act and reinforce the request and/or express appreciation for fulfilling the request (Mizuno, 1996a). Below are some of the categories in Japanese requests (pp. 94-95):

Guarantee/Limitation/Condition

Attempt to remove or reduce the hearer’s burden by limiting the request, providing certain conditions, or guaranteeing that the imposition will not be increased in the future:

issyuukan dakede iidesukara ‘Only one week will do’Getting a precommitment

Attempt to get a pre-commital:

jitsuwa cyotto onegaiga arundesukedo ‘Actually I have a small favor’Cost Minimizer

Indication of consideration of the burden to the recipient of the request while fulfilling the request:

moshi gomeiwakude nakereba ‘if it’s not too much trouble’Apology

Recognition of the imposition:

waruine, gomenne isogashiinoni ‘I feel bad, I’m sorry when you are busy’Entreaty

Reinforcement of the request:

nantoka onegai dekimasendesyouka ‘Could I please ask you [to fulfill the request] somehow’Reward/Contribution

Reward for the realization of the request:

kondo ohiru ogorukara ‘I’ll buy you lunch next time’Gratitude

Expression of appreciation:

arigatou gozaimasu, tasukarimasu ‘Thank you, that will be helpful’Grounder

Reasons for the request:

mou syuppan sarete naimitaide ‘it seems out of print now’

Above passages from Mizuno (1996a), pp. 94-95.

Request Perspectives

Similar to the situation with other languages (CCSARP project -- Blum-Kulka,

House, & Kasper, 1989), Japanese requests can also be classified

according to the perspective each request takes. By using the requester-oriented

verb, ![]() morau

‘to receive,’ the speaker emphasizes the role of the speaker

(

morau

‘to receive,’ the speaker emphasizes the role of the speaker

(![]() Mizuwo morae

masuka? ‘Could I get some water?’). On the other hand, the

use of the hearer-oriented verb,

Mizuwo morae

masuka? ‘Could I get some water?’). On the other hand, the

use of the hearer-oriented verb,  kureru

‘to give, or to let ~ have’, may stress the role of the hearer

(

kureru

‘to give, or to let ~ have’, may stress the role of the hearer

( Mizuwo kuremasuka? ‘Could

you give me some water?’).

Mizuwo kuremasuka? ‘Could

you give me some water?’).

Requests in Japanese employ multiple perspectives as they are represented

by the verb (e.g., ![]() kasu, ‘lend’ or

kasu, ‘lend’ or  kariru

‘borrow’) and the honorific language. The use of honorifics,

such as the hearer-oriented auxiliary verbs,

kariru

‘borrow’) and the honorific language. The use of honorifics,

such as the hearer-oriented auxiliary verbs,  kureru and

kureru and  kudasaru, and

the speaker oriented

kudasaru, and

the speaker oriented  morau and

morau and  itadaku, implies the speaker’s varying degree of deference.

itadaku, implies the speaker’s varying degree of deference.

The hearer-oriented verb,  kasu,

might be slightly more often used than the speaker-oriented verb,

kasu,

might be slightly more often used than the speaker-oriented verb,  kariru in all the situations regardless of the status or closeness

of the interlocutors. However, some combinations of these verbs with honorifics

auxiliary verbs are possible and almost equally common. For example,

kariru in all the situations regardless of the status or closeness

of the interlocutors. However, some combinations of these verbs with honorifics

auxiliary verbs are possible and almost equally common. For example,

Hearer-oriented verb

kasu + Speaker-oriented auxiliary,

morau or

itadaku:

Konohonwo kashite morae masuka?

konohonwo kashite itadake masuka? (more polite)Hearer-oriented verb

kasu + Hear-oriented auxiliary,

kureru or

kudasaru:

Konohonwo kashite kure masuka?

konohonwo kashite kudasai masuka? (more polite)

Above passages from Mizuno (1996b), pp. 66-68.

Alerters

The use of alerters (attention-getters) in Japanese plays an important role in getting the attention of the hearer and in preparing him/her for the upcoming request. One or more alerters tend to be used by native speakers in most request situations. Alerters are normally uttered casually for minor requests but prolonged with pauses for more serious major requests. Below are some of the most commonly used alerters:

|

|

Sumimasen(ga) ‘excuse me’ |

|

|

Ano(u) ‘um’ |

|

|

Shiturei shimasu/shitureidesuga ‘Excuse me’ |

|

|

...san (the name or title of the hearer) "Mr./Ms....’ |

|

|

greeting such as konnichiwa ‘hello’ |

|

|

cyotto |

Above passages from Kashiwazaki (1993), p. 56.

Variability of Requests

Japanese speakers would tend to vary their choice of request strategies

according to their relative status in relation to the recipient of the

request rather than the severity of imposition – behavior that has

been referred to as "person-oriented" communication

style (Mizutani,

1985). For instance, in interacting with those of lower status, a speaker

tends to use fairly direct request strategy types, while the speaker may

prefer much less direct strategies in speaking to those of higher status

than him/herself. Whereas the relative status of the interlocutors often

has an impact on the language use, the severity of imposition may have

little impact on the directness of the request. For instance, a request

in close or intimate relationship in Japanese tends to be casual (e.g.,

Okaasan, ocha! ‘Mom, [make me]

some tea!’; Rinnert,

1999) to show intimacy, which would probably be viewed as rude or unrefined

in English. However, in Japanese, a formal expression like

Okaasan, ocha! ‘Mom, [make me]

some tea!’; Rinnert,

1999) to show intimacy, which would probably be viewed as rude or unrefined

in English. However, in Japanese, a formal expression like  Ochawo kuremasenka? ‘Wouldn’t you give me some tea?’

or

Ochawo kuremasenka? ‘Wouldn’t you give me some tea?’

or  Sumimasenga ochawo itadake masendesyouka?

‘I’d hate to bother you but couldn’t I receive the favor

of your giving me some tea?’ would be considered inappropriate in

a close or intimate relationship. A minor request is not usually given

in a formal expression to a family member or close friend unless the speaker

is being sarcastic.

Sumimasenga ochawo itadake masendesyouka?

‘I’d hate to bother you but couldn’t I receive the favor

of your giving me some tea?’ would be considered inappropriate in

a close or intimate relationship. A minor request is not usually given

in a formal expression to a family member or close friend unless the speaker

is being sarcastic.

This is in contrast to a more "situation-oriented" style (Mizutani, 1985) as in American English where speakers are likely to vary their politeness level depending on the situation and the severity of the imposition. An American request at a dinner table would likely be Can/could you pass me the salt? In English, formal requests are often delivered politely with some sort of mitigation or politeness markers even in a close relationship.

References

Blum-Kulka, S., House, J., & Kasper, G. (1989). Cross-cultural Pragmatics: Requests and Apologies. Norwood, NJ: Alblex Publishing Corporation.

Hill, B., Ide, S., Ikuta, S., Kawasaki, A., & Ogino, T. (1986). Universals of linguistic politeness: Quantitative Evidence from Japanese and American English. Journal of Pragmatics, 10, 347-371.

Kashiwazaki, H. (1993). Hanashikake koudouno danwabunseki: Irai youkyuu hyougenwo cyuushinni [Discourse analysis of requests with phatic communication]. Nihongo Kyouiku [Journal of Japanese Language Teaching], 79, 53-63.

Mizuno, K. (1996a). ‘Irai’ no gengo koudouniokeru cyukangengo goyouron: Cyugokujin nihongo gakusyusya no baai [Interlanguage pragmatics in the speech act of request: The case of Chinese learners of Japanese]. Gengobunka Ronsyu 17(2), 91-106.

Mizuno, K. (1996b). ‘Irai’ no gengo koudouniokeru cyukangengo goyouron (2): Directness to perspective no kantenkara [Interlanguage pragmatics in the speech act of request: Directness and perspectives]. Gengobunka Ronsyu 18(1), 57-71.

Mizutani, N. (1985). Nichi-ei Hikaku: Hanashi Kotoba no Bumpoo [Comparison of Japanese and English Spoken Languages]. Tokyo: Kuroshio Shuppan.

Rinnert, C. (1999). Appropriate requests in Japanese and English: A preliminary study. Hiroshima Journal of International Studies, 5.

<< Return to Requests |

See Additional research >> |