Invitations in Spanish

Inviting is a very commonly used speech act among Spanish speakers around the world. In her 2008 article, Carmen García explains that the ways in which invitation sequences are carried out in Spanish may vary due to the personalities of the speakers involved along with their cultural backgrounds and beliefs. The act of inviting can be perceived as enhancing or threatening another's face, depending on the cultural values of those involved in the interaction. For instance, inviting can be considered face-enhancing for the hearer because the speaker shows s/he approves of the hearer and wants him/her to be included in the proposed activity. On the other hand, invitations, like requests, have some directive force, which could be perceived as face-threatening by the hearer because it imposes on his/her free will. The diverse cultural values of Spanish speakers in different communities around the world can influence which politeness strategies are preferred when issuing invitations (p. 270).

Classifying Invitation Strategies

The strategies utilized by speakers to carry out invitations can be classified into two main categories: Head Acts and Supportive Moves (Blum-Kulka et al, 1989). While a head act is considered the main unit used to issue an invitation, supportive moves accompany the head act and influence its effect through either aggravation or mitigation.

Following this framework, head acts can be further classified according to a continuum of directness-indirectness (Blum-Kulka et al, 1989). García (2008) points out that direct strategies as well as positive politeness strategies, which attempt to please the hearer, pertain to a system of solidarity politeness strategies (SPS). Indirect strategies along with negative politeness strategies, which seek to avoid imposing on the hearer, are classified according to a system of deference politeness strategies (DPS).

- Solidarity politeness strategies imply less distance between conversational partners and are used to demonstrate camaraderie and solidarity.

- Conversely, deference politeness strategies imply more distance between the conversational partners and are used to demonstrate formality and respect.

Because supportive moves can either increase or weaken the force of an invitation, they can be further categorized as either aggravators or mitigators (García, 2008, p. 272-273).

Invitation Strategies in Argentinean and Venezuelan Spanish

García's 2008 article demonstrates that invitations in Argentinean and Venezuelan Spanish can be divided into three stages:

1. Invitation-Response

In this first stage, the following strategies can be used to issue an invitation among Venezuelan and Argentinean Spanish speakers (García, 2008, p. 285).

Solidarity politeness strategies (SPS)

- Mood derivableIn mood derivable strategies, the grammatical mood of an utterance reflects the speaker's intention. With invitations, the imperative form is typically used.

Ex: sí, venite más o menos a las 8 p.m.

'yes, come more or less at 8 p.m.'

(García, 2008, p. 275) - Explicit performativeExplicit performative strategies make an explicit reference to the speaker's intention.

Ex: y así te invito así no (te tengo que) llamar y así.

'and then I invite you so (I don't have to) call and so.'

(García, 2008, pp. 275-276) - Obligation statementObligation statements make reference to the hearer's obligation to participate in the act.

Ex: y tienes que venir.

'and you have to come.'

(García, 2008, p. 276) - Locution derivableIn locution derivable strategies, the intention of the speaker is derived from the meaning in the utterance.

Ex: vas a venir?

'are you going to come?'

(García, 2008, p. 276) - Want statement/questionWant statement/question strategies make reference to the speaker's desire for the intended action to be carried out.

Ex: quiero que vengas

'I want you to come'

García, 2008, p. 276)

ImpositivesImpositives, or directives, are the most direct strategies used to show solidarity politeness (García, 2008, p. 272).

Deference politeness strategies (DPS)

- Suggestory formulaSuggestory formula strategies rely on the use of suggestions for the proposed action to occur.

Ex: sí, mira y tú a propósito por qué no vienes?

'yes, look and you by the way why don't you come?'

(García, 2008, p. 279) - Query preparatoryQuery preparatory strategies make reference to a condition that is necessary for the proposed action to occur, such as willingness or ability.

Ex: tú tienes tiempo el sábado?, de ir?

'Do you have time on Saturday?, to go?'

(García, 2008, p. 279) - Strong hintStrong hint strategies make reference to elements related to the intended act, yet the intention of the speaker is not explicit in the utterance.

Ex: el sábado cumplo años, no sé si te acordás…

pero bueno voy a hacer así en casa una fiesta…

'my birthday is on Saturday, I don´t know if you remember…

but well I am going to have a party in my house…'

(García, 2008. p. 280)

Conventionally indirectConventionally indirect strategies make reference to a condition that is necessary for the act to be carried out. These strategies often include suggestions or refer to the hearer's ability or willingness to participate in the action (García, 2008, p. 272).

Non-conventionally indirectNon-conventionally indirect strategies are dependent on contextual clues in order to carry out the action. They tend to be vague and non-specific, including strong or mild hints (García, 2008, p. 272).

Mitigators

Ex: mirá, te quería decir algo

'hey, I wanted to tell you something'

(García, 2008, p. 281)

Ex: va a ser a todo dar. mis veintiún años por favor, tengo que celebrarlos.

'it is going to be a big one. my twenty first birthday please, I have to celebrate it.'

(García, 2008, p. 282)

Ex: el sábado, el sábado a la noche, para comer algo, unas cervecitas y bueno…

'Saturday, Saturday at night, to eat something, some beer and well…'

(García, 2008, p. 281)

Ex: sí, bueno porque es mi cumpleaños y pienso hacer una reunión, pero nada así, del otro mundo, pero es una reunión familiar

'yes, well because it is my birthday and I am thinking about having a party, but nothing big, of the other world, but it's a party [with the] family.'

(García, 2008, p. 282)Aggravators

Ex: y bueno, es importante que vos estés

'and well it is important that you be there'

(García, 2008, p. 283)

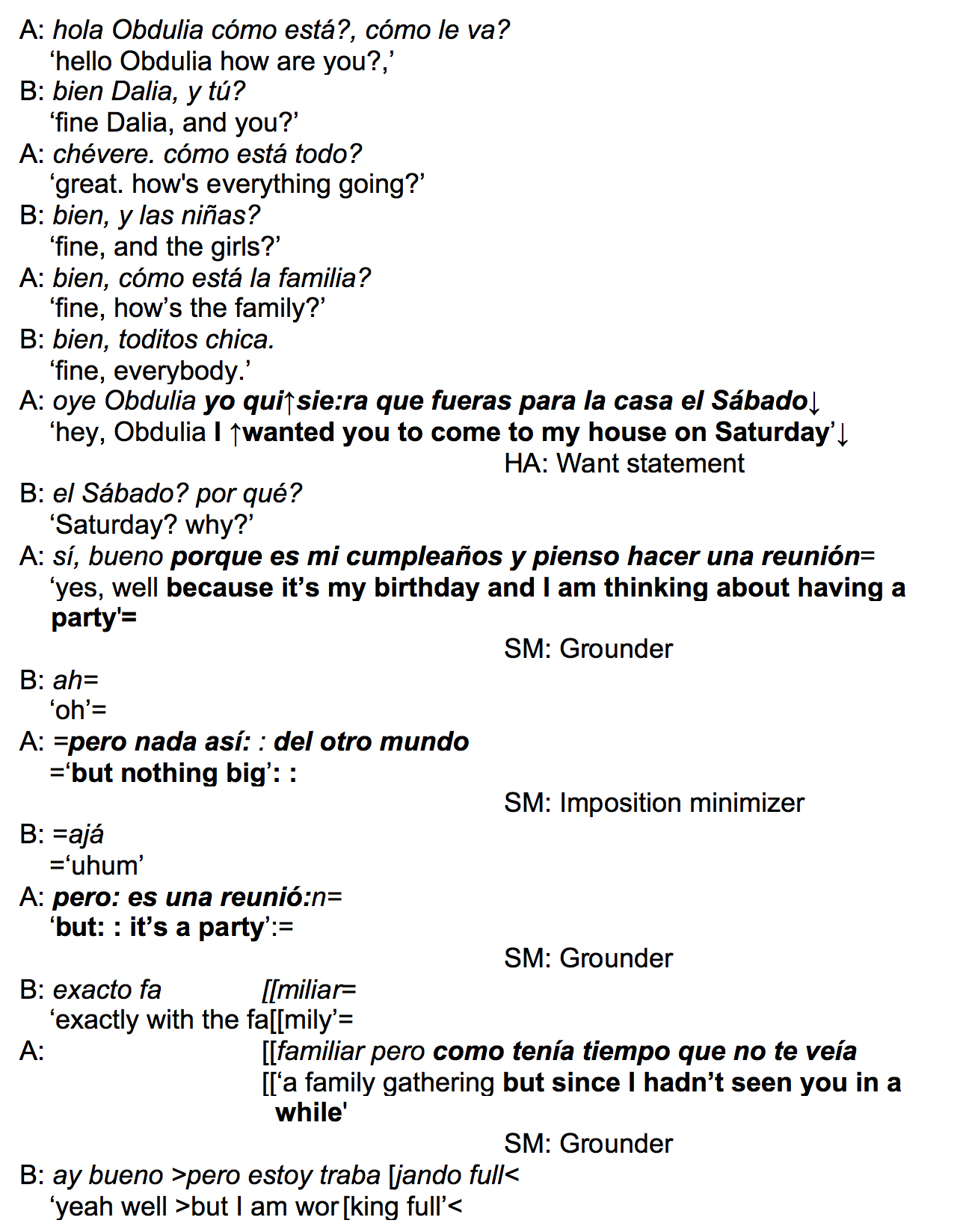

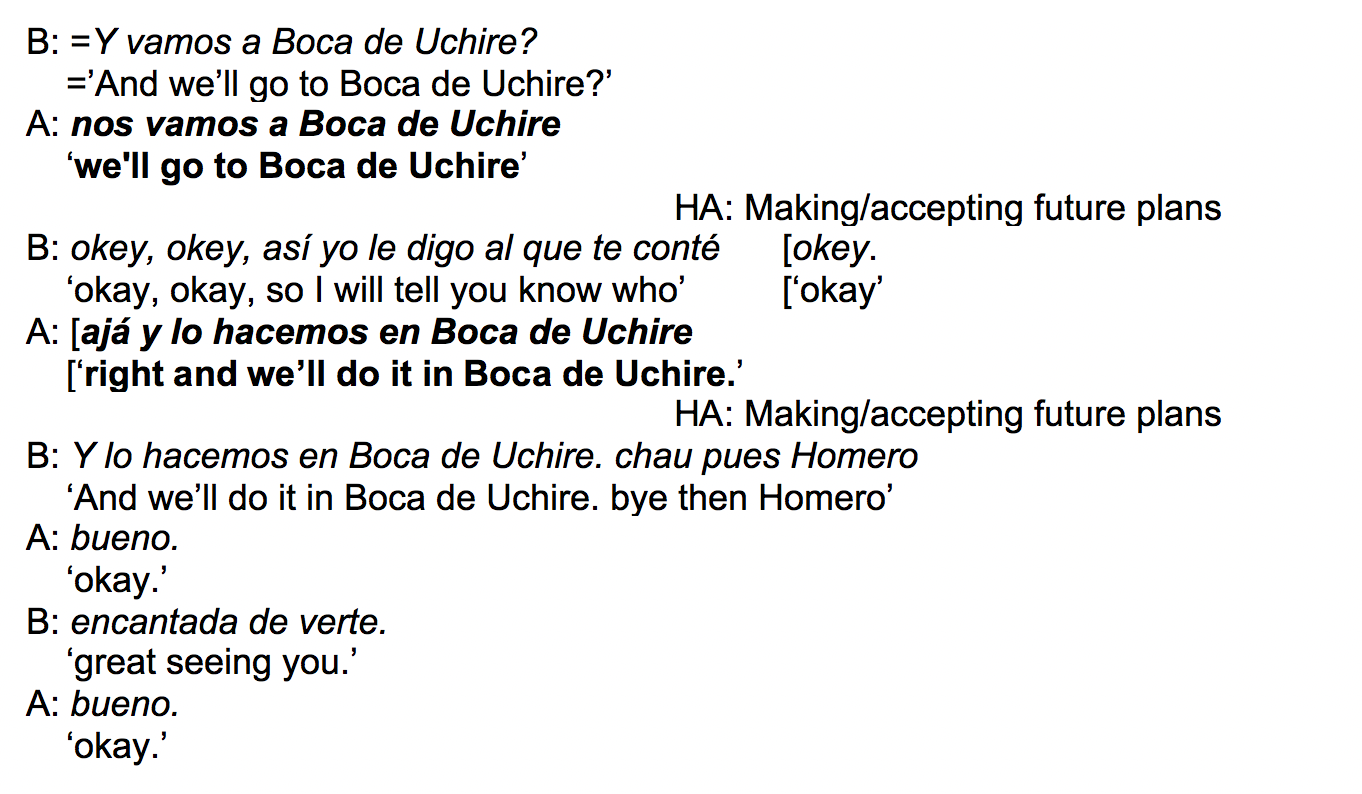

The following example from García (2008, p. 284) demonstrates an invitation-response interaction between two Venezuelan Spanish speakers, with the head acts (HA) and supportive moves (SM) labeled:

[[ simultaneous utterances |

In her 2008 article, García reveals that in the invitation-response stage, both Argentinean and Venezuelan Spanish speakers demonstrated a slight preference for solidarity politeness strategies to show approval of the conversational partner and display a close relationship. Nevertheless, they do employ deference politeness strategies so that the invitation seems less imposing. While both groups use these similar strategies when inviting, some differences in strategy preferences were revealed. For example, Argentineans tended to use more locution derivable and explicit performative strategies, suggesting that they are more direct when issuing invitations. Furthermore, Venezuelans' frequent use of want statements suggests that they may be more open to a refusal from their conversational partner .

With respect to supportive moves, both cultural groups prefer using mitigators over aggravators. However, Argentineans prefer to entice their conversational partners by giving additional information about the invitation, while Venezuelans tend to promote their invitation with grounders such as justifications, excuses, and reasons (Garcia, 2008).

Gender Differences in Venezuelan Spanish Speakers in the Invitation-Response Stage

In the first stage of invitation-response, some differences arise when comparing preferences between male and female Venezuelan Spanish speakers.

See García, 1999 for details of gender differences in Venezuelan Spanish.

- For an example of obligation statement from a Venezuelan female speaker and a friend, see García, 1999, p. 397.

- For an example of want statement from a Venezuelan male speaker and a friend, see García, 1999, p. 399.

2. Insistence-Response

García (2008) states that the insistence-response stage occurs after the invitee rejects the invitation and ends when the inviter accepts the rejection. In this second and most involved stage of inviting, the following strategies can be used among Venezuelan and Argentinean Spanish speakers (p. 290).

Head acts using request strategies

This category of head acts includes strategies used to request information, in contrast to non-request head acts that do not seek additional information.

Solidarity politeness strategies (SPS)

- Mood derivable

- Explicit performative

- Obligation statement

- Concealed commandConcealed commands can be used by speakers to assert something to the hearer, thus supporting their insistence.

Ex: eh el sábado por la noche nos reunimos, si te vas, no sé, te vas el domingo, no sé algo, vas otro fin de semana.

'ah Saturday night we're getting together, if you leave, I don't know, go on Sunday, I don't know, do something, go another weekend.'

(García, 2008, p. 276) - Locution derivable

- Want statement/question

Impositives

Deference politeness strategies (DPS)

- Suggestory formula

- Query preparatory

Conventionally indirect

Non-request head acts

Solidarity politeness strategies (SPS)

Ex: A: voy a tratar, pero la verdad que lo veo difícil porque ya lo arreglé la semana pasada para ir

'I will try, but the truth is I see it difficult to comply because I made arrangements to go last week'

B: bueh 'ta bien, cualquier cosa: : me avisás

'well it's ok, anythi: :ng let me know'

(García, 2008, p. 277)

Ex: A: de cualquier manera si yo puedo llegar a escaparme, sabés que voy

'anyway if I can get out of it, you know I will go'

B: bueno, no, tampoco quiero provocar un inconveniente en el trabajo ni mucho menos, pero bueno yo te avisaba obviamente no me gustaría que después te enteraras

'well, no, I don't want to cause a problem at work at all, but well I was letting you know, obviously I wouldn't like you to find out later'

(García, 2008, p. 277)

Ex: A: sabés que me voy a Córdoba

'you know I am going to Córdoba'

B: no, no, me estás jodiendo

'no, no, you are bothering me'

A: no, de veras

'no, really'

(García, 2008, p. 277)

Ex: claro, pero quién es esta chica? tu novia te dice algo y tenés que ir?

'of course, but who is that girl? Your girlfriend tells you something and you have to go?'

(García, 2008, p. 278)

Ex: A: sabes que se casa mi hermano

'you know my brother is getting married'

B: a qué hora se casa tu hermano?

'at what time is your brother getting married?'

(García, 2008, p. 278)- Emotional appeal

Ex: ay: : no. mirá sabés que vos sos una persona importante, sabés que están, sabés que te esperan

'o: : h no. see you know you are an important person, you know they are, you know they are waiting for you'

(García, 2008, p. 278)

Ex: tú sabes que este sábado es mi cumpleaños. tengo una fiesta pero tienes que ir Obdulia, va a ser una fiesta a todo dar, va a ser en en en la en la Quinta Esmeralda, en la Quinta Esmeralda imagínate

'you know that my birthday is this Saturday Obdulia. I am having a party but you have to go Obdulia, it's going to be a big one, it's going to be at the Quinta Esmeralda, at the Quinta Esmeralda imagine that'

(García, 2008, p. 278)

Deference politeness strategies (DPS)

- Grounder

- Imposition minimizer

Ex: A: te soy sincera. no puedo porque ya tengo otro compromiso.

'I'll be honest with you. I can't because I have already make other plans.'

B: a: y cuánto lo siento

'o: h I'm very sorry.'

(García, 2008, p. 281)

Supportive moves

Mitigators

- Grounder

Ex: bueno, sí, 'ta bien. no no hay drama

'well, yes, that's ok, no there's no drama'

(García, 2008, p. 282)- Providing information

- Promising reward

Aggravators

- Emotional appeal

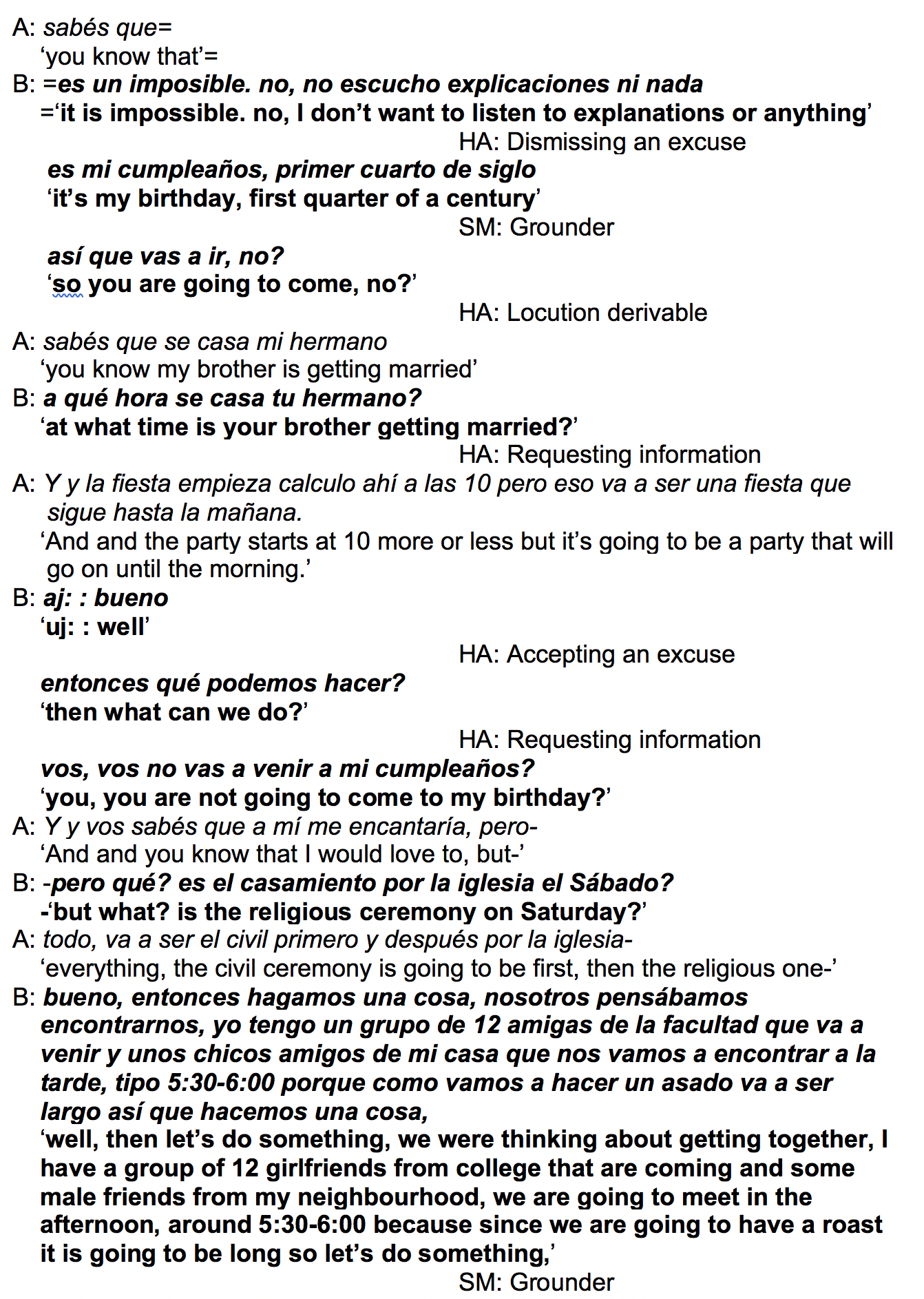

The following example from García (2008, pp. 287-288) demonstrates an insistence-response interaction between two Argentinean Spanish speakers, with the head acts (HA) and supportive moves (SM) labeled. This example reflects a great deal of insistence from the inviter, which does not appear to be imposing to the conversational partner.

When comparing the strategy preferences between Argentineans and Venezuelans in the second stage of insistence-response, some differences arise. In this sense, Argentineans in García's 2008 study tended to use a larger quantity and wider variety of strategy types, which strengthened their insistence. Similarly, with respect to head acts that do not correspond to request strategies, Argentineans utilized almost only solidarity politeness strategies (93%), while Venezuelans used these only 52% of the time.

The reactions to excuses given also reveal differences between the two cultural groups. For instance, Argentineans tended to both accept and dismiss excuses, while in general Venezuelans solely dismissed them. In addition, Argentineans often sought additional private information regarding the reasons why the conversational partner declined the invitation, yet Venezuelans hardly requested more information or justifications for the refusal.

With regards to supportive moves, mitigators were preferred by both cultural groups. Argentineans solely used mitigators, whereas Venezuelans preferred them 87% of the time, with some aggravators (13%). Like the invitation-response stage, Argentineans enticed their conversational partners by offering more information, yet Venezuelans preferred to provide reasons (or grounders) to show why they were inviting (p. 287-291).

Gender Differences in Venezuelan Spanish Speakers in the Insistence-Response Stage

Additional differences are seen between male and female speakers of Venezuelan Spanish in the second stage of insistence-response. See García, 1999 for details of her findings.

- For an example of expression of sorrow from a Venezuelan female speaker and a friend, see García, 1999, pp. 404-405.

- For an example of dismissal of excuse from a Venezuelan male speaker and a friend Male (VM), see García, 1999, p. 403.

3. Wrap-Up

In García's 2008 article, she holds that the wrap-up stage occurs when the invitee's rejection is accepted by the inviter. In this third stage, the following strategies can be used to wrap up an invitation (p. 294).

Head acts using request strategies

Solidarity politeness strategies (SPS)

- Mood derivable

- Locution derivable

Impositives

Deference politeness strategies (DPS)

- Suggestory formula

Conventionally indirect

Non-request head acts

Solidarity politeness strategies (SPS)

Ex: vamos a hacer ésta, vamos a celebrar, vamos a hacer otra celebración

'we are going to do this one, we are going to celebrate, we are going to have another celebration.'

(García, 2008, p. 278)

Ex: A: porque: no, porque mis hi: jas tú sabes yo no tengo con quien deja: rla, y 'tonces en la noche, vivo muy legos y me complica,

'becau: se no, because my daugh: ters you know I don't have anyone to lea: ve her with, and then at night, I live very far and it gets complicated,'

B: ay, bueno, bueno qué lástima!

'ah, okay okay what a shame'

(García, 200, p. 279)Deference politeness strategies (DPS)

Ex: bueno la verdad es que una cosa así es muy ( ) lo que pasa es que se trataba de ti, pero bueno no importa, nos hablamos luego

'well the truth is that something like that is very ( ) what happens is that it was about you, but then it doesn't matter, we'll talk later.'

(García, 2008, p. 280)- Expressing sorrow

Supportive moves

Mitigators

- Minimizing disappointment

- Grounder

- Providing information

- Promising reward

Aggravators

- Emotional appeal

Ex: A: ay Yadira. bueno es que se me hace muy difícil. de repente lo celebramos la otra semana, el tuyo. seguimos la rumba y nos vamos de feria.

'oh Yadira. Well it's that it's very difficult for me. We can probably celebrate yours next week. We will continue the party and go to have a good time.'

B: pero vas a tener que pagar tú

'but you will have to pay'

A: ah bueno, por supuesto. ése es tu regalo.

'oh well, of course. That will be your present.'

(García, 2008, p. 283)

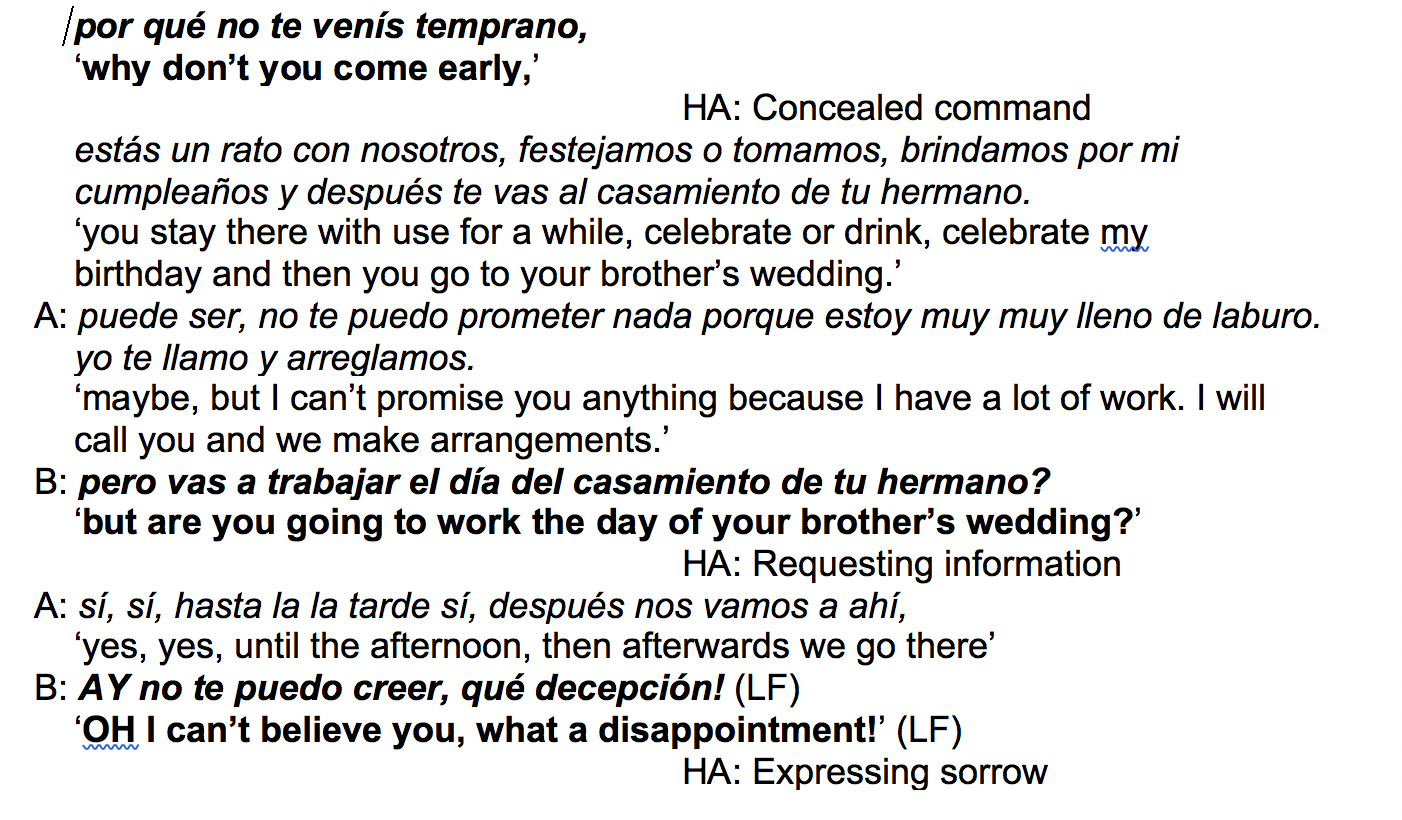

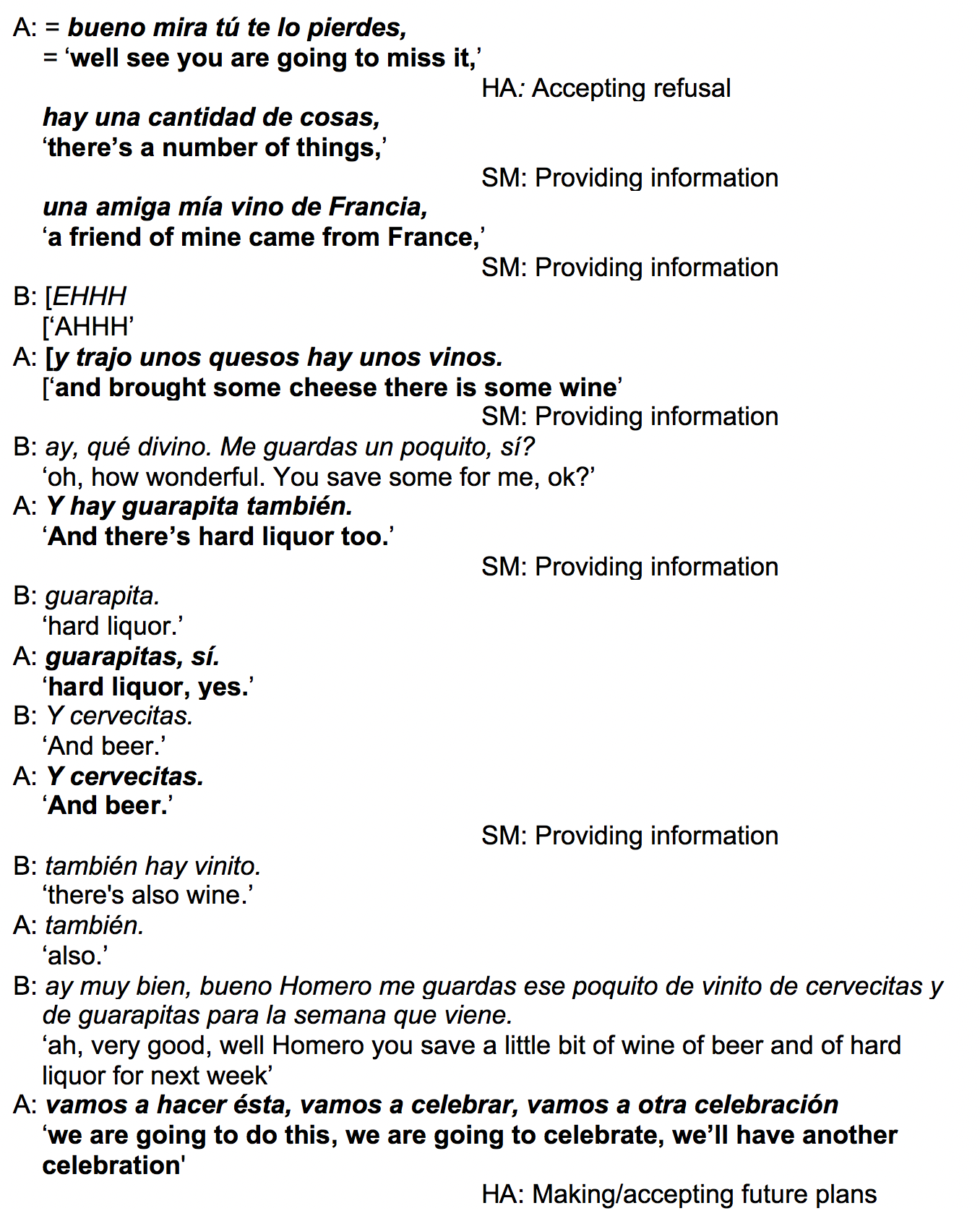

The following example from García (2008) demonstrates a wrap-up interaction between two Venezuelan Spanish speakers, with the head acts (HA) and supportive moves (SM) labeled. Although the invitation is rejected, this example reflects the friendly nature of closing the conversation.

García (2008) outlines a number of differences in the strategies preferred between Argentineans and Venezuelans in the wrap-up stage. For instance, though Venezuelans tended to be wordier and used a larger number of strategies in this stage, they did not use request/inviting strategies, while Argentineans did and were less verbose. With regards to non-request head acts, Argentineans used very few and only in the making/accepting future plans category. In addition to making/accepting future plans, Venezuelans also largely expressed sorrow, did not indebt the conversational partner (DPS), and accepted the refusal (SPS), unlike Argentineans (p. 293-299).

Because of these differences, García (2008) argues that pragmatic failure could potentially occur in interactions between individuals from these two cultures. For instance, Venezuelans could feel pressured to accept invitations by Argentineans, who leave less opportunity for refusal. Likewise, since Venezuelans often attempt to demonstrate respect by allowing their conversational partners to refuse an invitation, Argentineans could interpret their intentions for the invitations as less sincere.

With respect to supportive moves, the two cultural groups preferred different strategies in this last stage. Similar to the first two stages, Argentineans tended to utilize only mitigators, many of which included enticing the conversational partner with additional information. However, a majority of the supportive moves given by the Venezuelans were often aggravators, including emotional appeal and indebting the conversational partner (García, 2008, p. 293-299).

Gender Differences in Venezuelan Spanish Speakers in the Wrap-Up Stage

Although both male and female participants were found to prefer solidarity politeness strategies in the wrap-up stage of invitations, there were a number of differences between the two groups.

See García, 1999 for details of the gender differences in invitations issued by Venezuelan Spanish speakers.

- For an example of acceptance of refusal from a Venezuelan female and a friend, see García, 1999, p. 407.

- For an example of promise of future encounter from a Venezuelan male speaker and a friend, see García, 1999, p. 407.

Summary of Argentinean and Venezuelan Invitation Strategy Preferences

Overall, both cultural groups represented in García's 2008 study demonstrated a preference for solidarity politeness strategies, particularly Argentineans. This reflects the intimate nature of the relationship between those involved in the invitation exchanges. Nevertheless, the fact that Venezuelans utilized deference politeness strategies to a larger extent suggests they may be more reluctant to impose, opting for negotiation that establishes both respect and camaraderie. As for supportive moves, mitigators were preferred by both groups, and almost exclusively for Argentineans, who used additional information to entice their conversational partners. The majority of Venezuelans preferred to give reasons and justifications for the invitation, rather than providing more information (2008, p. 294-295).

Invitations in Peninsular Spanish

While in some cultures inviting may be perceived as face-threatening by implying pressure for the invitee to accept the invitation, Nieves Hernández Flores (2001) argues that this is not necessarily the case in Spain, where offering and inviting are more likely to be considered as demonstrating solidarity and affection between those involved in the interaction (p. 30).

In her 2001 article, Hernández Flores outlines a number of strategies that can be used to issue offers and invitations during colloquial conversations between family and friends in Spain.

- Neutral strategies:Hernández Flores (2001) considers direct strategies like imperatives along with query preparatory strategies that inquire about willingness/ability to be "neutral" invitation strategies in Peninsular Spanish because they do not contain any features of linguistic politeness (or impoliteness). For instance, if the invitation were refused, it would not cause the speaker or hearer any discomfort, and if it were accepted, it would not require additional work from either conversational partner (p. 32).Strategies employed in interactions that cannot be considered as either polite or impolite.

Ex: Pili: siéntate, Elsa.

'sit down, Elsa'

(Hernández Flores, 2001, p. 31)Ex: Verónica: ¿queso? ¿queréis queso?

'cheese, do you want cheese?'

Gabriel: no, yo tengo ya.

'no, I already have'

(Hernández Flores, 2001, p. 32) - Encouragement:

The use of expressions such as "hala," common forms of address, and repetition are strategies that can encourage acceptance of the invitation.

Ex: Celia: ¡hala! Sentaros, hijos, aquí!

'come on! sit down my dears, here!'

Ex: Pili: Verónica, échate chichas pa' probar…échate, échate…

'Veronica, have some 'chichas' to taste, have some, have some…'

(Hernández Flores, 2001, p. 33)

- Diminutives:

Using diminutives in Spanish (adding the morpheme -ito) can serve to mitigate the force of an invitation and make it more attractive to the invitee.

Ex: Pili: ¿quie- quieres ahora? sobraron, esta mañana unas sopas de fideos.

¿no las quieres calentitas?

'do you, do you want now? there is some noodle soup from this afternoon. don't you want it warm-(diminutive)?'

(Hernández Flores, 2001, p. 33)

- Negative Questions:

By posing a negative question, the speaker implies a positive response and persuades the invitee to accept an offer that s/he considers attractive or beneficial to the conversational partner.

Ex: Pili: ¿no las quieres calentitas?

'don't you want it warm-(diminutive)?'

(Hernández Flores, 2001, p. 33)

- Form of Probability:

An offer can be softened by using an adverb such as "quizás" (perhaps) or a verb in the future tense.

Ex: Pili: ¿quieres…? Esto…café sí querrás, ¿no?

'you want…some…ahh…coffee, don´t you?'

(Hernández Flores, 2001, p. 34)

- Locutional Form of Imposition: The speaker gives the hearer something without making an offer beforehand, as s/he believe that it will benefit the conversational partner. In the example below, Pedro serves his guest wine without offering it first.

Ex: Pedro: ¡éste es un vino riquísimo!

'this is a delicious wine'

(Hernández Flores, 2001, p. 34)

Hernández Flores (2001) argues that after an invitation is issued, the invitee can 1) accept it, 2) reject it because of lack of interest in the offer, or 3) reject it with the hope of it being reissued. The following examples demonstrate each of these strategies.

- Accept invitation:

Ex: Patricia: María, ¿tú quieres más?

'María, do you want more?'

María: ¡bueno, sí! ¡pero no te levantes! ¡no te levantes! (Patricia stands

up) ¡jo! Un poco si hay, un poco. Están mu' ricos.

'okay…! but don't stand up! don't stand up! A bit if there is some, a

bit, this is delicious'

(Hernández Flores, 2001, p. 35) - Reject invitation because of no interest in offer:

Ex: Pili: (To Rosalia and Celia) ¡comed, comed mandarinas, que están mu' buenas! ¡anda!

'eat, eat some mandarins, they are so good! come on!'

Rosalia: ya me he comido dos, =

'I've already eaten two'

Pili: no, pues cómete más =

'then, eat some more'

Rosalia: =no me voy a comer otra…

'I won't eat another one…'

Pili: =que están mu' buenas

'but they are very good'

(Hernández Flores, 2001, p. 36) - Ritual refusal (reject invitation with hope of it being reissued):Please see Chinese Refusals for further information and examples of ritual refusals.

Ex: Celia: ¡hala! ¡sentaros, hijos, aquí!

'come on! sit down my dears, here!'

Pili: ¡buh, madre mía, pero si es que yo de verdad, estás ahí con tu

hermana y dirá tu hermana que a qué…!

'oh, dear, but I really, you are there with your sister and your sister maybe says why…!'

Celia: ¡que no! ¡mi hermana no dice nada!

'no, really! my sister doesn't say anything!'

Pili: sí, que a qué hora hemos venido…

'yes, she will say that we came at a late hour…'

Celia: ¡no, no, no! mira, ha venido hoy a pedirme, que la ayudara un poco,

='no, no, no! look, she has come today to ask me to help her a bit,'

Pili: ya

'I see'

Celia: = pa' echarla una mano,

to lend her a hand,'

(Hernández Flores, 2001, pp. 35-36)

To summarize, Hernández Flores (2001) holds that solidarity between the conversational partners is the principal way in which politeness is demonstrated in invitations in colloquial Peninsular Spanish. To achieve and maintain solidarity, speakers can simply make an invitation, use encouragement, diminutives, and other strategies to insist that the offer is accepted. Doing this among friends and family members does not appear to threaten face, as it does in other cultures. In this sense, Peninsular Spanish speakers appear to be less concerned about imposing on their conversational partners than speakers from other cultures (p. 37-38).

References

Blum-Kulka, S., House, J., & Kasper, G. (Eds.). (1989). Cross-cultural pragmatics: Requests and apologies. Norwood: Ablex Publishing Corp.

García, C. (1999). The three stages of Venezuelan invitations and responses. Multilingua:

Journal of Cross-Cultural and Interlanguage Communication, 18(4), 391-433.

García, C. (2008). Different realizations of solidarity politeness: Comparing Venezuelan

and Argentinean invitations. In K. P. Schneider & A. Barron (Eds.), Variational pragmatics: A focus on regional varieties in pluricentric languages (pp. 269-305). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Hernández Flores, N. (2001). Politeness in invitations and offers in Spanish colloquial

conversation. Language & Cultural Contact, 28, 29-40.

<< Return to Invitations |

See Teaching Tips >> |