Spanish Immersion and the Academic Success of Alamo Heights Students

The ACIE Newsletter, November 2005, Vol. 9, No. 1

Dr. Cordell T. Jones, Principal, Woodridge Elementary, Alamo Heights Independent School District, San Antonio, Texas

he primary goal of this research investigation was to examine whether or not the Alamo Heights Independent School District (AHISD) Spanish Immersion Program accelerates or hinders students’ academic success relative to same-district, non-immersion peers. Statistical comparisons were made in 2003, using the ability and achievement test outcomes of 168 students in the Spanish Immersion Program receiving curricular instruction in a second language, Spanish, and 832 students not in the Spanish Immersion Program who received their curricular instruction in English.

At the time of this study (fall 2003), the Spanish Immersion

Program in AHISD was beginning its 6th year of operation.

This program begins in 1st grade and continues through the

5th grade as self-contained classes. Spanish immersion is

offered in both elementary schools in the district (Cambridge

Elementary and Woodridge Elementary) and is designed for native

English-speaking students who want to learn a second language.

Students are selected via a lottery system since there are

more students wanting into the program than slots available.

The program uses the early total immersion model and English

is introduced during the second semester of second grade for

30 minutes. In third grade, thirty to forty-five minutes of

English instruction is offered, and in grades 4 and 5, there

is one hour of English instruction provided.

Upon entering the Alamo Heights Junior School, the immersion

offerings for students change. In grade 6, social studies

and science are taught in Spanish. The following year social

studies and language arts are taught in Spanish, and in 8th

grade, students take Spanish II Pre-Advanced Placement as

their Spanish language course.

As of 2005 the district’s demographic indicators report 1,671 students in grades 1-5 (K students are not eligible for the program and attend another school). The vast majority are white (66%) or Hispanic (31%) and nearly one quarter are economically disadvantaged and qualify for free and reduced lunch services. The ethnic background of Spanish immersion students typically mirrors that of non-immersion students; however, the economically disadvantaged population attending the Spanish immersion classes tends to be somewhat lower than that found in the rest of the school.

Study Design

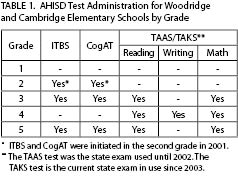

Data from three success variables were collected on students during the 2002-2003 school year. Success variables included the Cognitive Abilities Test (CogAt), one criterion-referenced test given to most Texas public school students –the Texas Assessment of Academic Skills (TAAS) or the Texas Assessment of Knowledge and Skills (TAKS), and the third administered annually by AHISD–the Iowa Test of Basic Skills (ITBS). The ITBS is a norm-referenced test that can be taken along with the matching CogAT to compare ability with actual academic performance. Table 1 indicates at what grade levels the tests are given.

Since achievement outcomes of immersion and non-immersion student groups were being compared, it was important to determine if the students in the two groups had similar or different cognitive abilities prior to starting the Spanish-medium and English-medium programs. Certainly, one would speculate that Spanish immersion students would outperform non-immersion counterparts were cognitive ability differences found. Because of this, data were analyzed using two different types of comparison analyses, independent samples t-tests and Analysis of Co-Variance (ANCOVA). Independent samples t-tests were carried out when findings from CogAT analyses indicated no difference in cognitive ability between the two groups of students. Alternatively, once evidence of cognitive ability difference was present, to ensure appropriate statistical inferences, the ANCOVA test was used. In this manner, initial ability differences were compensated for prior to making academic achievement comparisons.

Study Findings

Research Question 1

Is student ability different between students participating

in the Spanish Immersion Program and those in English-medium

classes in two AHISD elementary schools in San Antonio, Texas?

CogAT results indicated that there was a difference between

student ability when comparing the Spanish Immersion Program

students to non-Spanish Immersion Program students. In seven

of the twelve statistical analyses (58%) of the CogAT results,

students in the two groups demonstrated different cognitive

abilities—at times the immersion students scored higher

and at times the non-immersion. In the remaining five cases

(42%), no cognitive differences were found.

Research Question 2

Is academic achievement different between those students participating

in the Spanish Immersion Program and those students in English-medium

classes in two AHISD elementary schools in San Antonio, Texas?

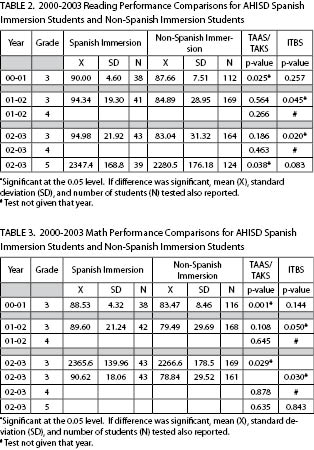

The results of this study showed that the academic achievement

of students participating in the AHISD Spanish Immersion Program

is similar to or greater than non-immersion students attending

the same elementary school (see Tables 2 and 3 below). Eight

of a total of 24 (33%) tests run (twelve tests for each of

two measures) were statistically significant at the 0.05 level.

In all eight cases (100%), students in the Spanish Immersion

Program outperformed non-Spanish immersion counterparts. Of

the twelve analyses conducted on data from the TAAS/TAKS Texas

state assessments, four (33%) indicated statistical significance.

Four of the twelve comparative analyses (33%) on the district’s

ITBS also indicated statistical significance.

Discussion of Findings

Any time a change in programming occurs within a district, it is reasonable for parents and educators alike to raise concerns about academic performance. This study was intended to serve as basic research for AHISD in order to evaluate student achievement within the district’s Spanish Immersion Program. Achievement measures consisted of standardized test results from two district- and statewide measures. AHISD Spanish immersion students’ performance on the TAAS/TAKS, and ITBS tests indicate that these students are achieving as well as or better than non-immersion peers after adjusting for differences in cognitive ability. These findings lend additional research-based support to immersion education’s long-standing academic success record. Clearly, there are substantial academic achievement benefits for elementary students learning a second language through immersion programming. Moreover, there appeared to be no significant lags in these immersion students’ English development.

In the past researchers have found that early total immersion students may experience a lag in certain areas of English language arts prior to the introduction of this content area in the curriculum (typically in grades 2 or 3). However, these results appear to indicate that given appropriate support in the home and community language environment, English-speaking students’ primary language growth can continue effectively during the K-2 years even though instruction in the primary language is minimal to non-existent during that time. Such findings provide affirming evidence for the district’s decision to begin the program at the elementary level and start students’ second language learning early.

While the achievement evidence provides gratifying confirmation of academic benefits, educators in AHISD hope this program results in global and local community benefits as well. As the world continues to evolve into a global society, students who can communicate in a second language may be better positioned to acquire levels of enhanced intercultural understanding and thus, be able to play a more effective role in the increasingly interdependent world community (Fortune, 2002). Currently, the U.S. is the only industrial nation that does not emphasize learning a foreign language in the primary grades (NEA Today, 1999).

Historically, cultures have bridged conceptual obstacles by

learning each other’s language. Melikoff (1972) mentions

the benefits of a Canadian French immersion program that helped

English-speaking students learn French. The result was an

increase in appreciation of and interaction between two Canadian

cultures, the Francophone and the Anglophone. Earlier, in

U.S. history, Genesee (1987) reminds us that the immigration

boom created the need for immigrants to learn English and

for U. S. citizens to learn Spanish, Italian, French and German.

Currently in the U.S., the need to interact and communicate

with individuals from diverse linguistic and cultural backgrounds

is of national importance. Los Angeles County, the largest

county in the country, reports over 150 different racial and

ethnic groups (Clinton, 1996). According to Fix and Passel

(2003) of the Urban Institute, one in five students in U.S.

elementary and secondary schools are children of immigrants,

most of whom speak a home language other than English. These

numbers are likely to increase as these demographic researchers

project the entry of an additional 14 million immigrants between

2000-2010, barring any unforeseen changes in immigration policy

and economics.

AHISD hopes that the Spanish Immersion Program can make inroads and begin to bridge the gap between this community’s local English-speaking and Spanish-speaking cultures. By learning Spanish, English-speaking children now have the ability to interact with Spanish-speaking children in the schools and community. Such interactions and connections may, in turn, foster more appreciation of diverse backgrounds and intercultural understanding within our local and national community.

Summary Conclusions and Recommendations

The following are recommendations offered to the district for consideration based upon a summary of the study findings.

The data in this study clearly indicate that the Spanish Immersion

Program, as implemented at Cambridge and Woodridge elementary

schools in AHISD, is successful as defined by the constructs

of this study. Out of 24 comparison analyses run, there is

not one, with any statistical significance, in which the non-Spanish

immersion students outperformed students in the Spanish Immersion

Program. As a result, it is recommended that this program

continue.

Further, it is clear that the curriculum provided for the

students in their second language is adequate to keep them

academically on track or exceed their non-Spanish immersion

counterparts.

The data indicate that students learning a second language can effectively demonstrate academic success in their native language, even when instruction in that language is temporarily suspended. In other words, students with little or no English-medium instruction can adequately pass a standardized achievement test given in English.

Clearly, the Spanish Immersion Program students are experiencing academic success. The curriculum and their teachers also appear to be moving students towards bilingualism and biliteracy. However, to date students’ immersion language proficiency development remains an area in need of assessment. Evaluating immersion students’ Spanish proficiency and determining benchmarks for expected levels of Spanish proficiency is an area recommended for future research within the program.

An Addendum to the Study

In spring 2004, 31 seventh grade Spanish immersion students took the National Spanish Examination, an exam intended to evaluate the Spanish skills of high school students. Results were as follows: Twenty students (65%) scored in the 90th national percentile, five students (16%) scored in the 80th national percentile, four students (13%) scored in the 70th national percentile, and two students (6%) scored at the 67th national percentile. In addition, one of these 7th graders scored in the 99th national percentile and was ranked 3rd out of 3243 students nationally. We believe we have much cause to celebrate both the academic and linguistic achievements of AHISD Spanish immersion students!