Comparison Contexts:

African-American Students, Immersion

and Achievement

The ACIE Newsletter, May 2005, Vol. 8, No. 3

by Michelle Haj-Broussard, Assistant Professor of Teacher Education, McNeese State University, Lake Charles, LA

|

In dual language education much research has focused on the acquisition of academic content or the acquisition of language. However, as Valdes (1997) argued, dual language education does not occur in a sociocultural vacuum. Rather, it reflects the contexts and power structures within which it exists. In the U.S. dual language education confronts the national dilemma of a majority/minority student achievement gap. In the South, this dilemma is known as the Black/White Achievement Gap. This study examines the Black/White Achievement Gap in a very specific sociocultural context—Southwestern Louisiana—where many African-American students also have francophone cultural heritage.

The Black/White Achievement Gap is an issue that cannot be

overlooked. Hedges and Nowell (1998) determined that there

is still a significant gap in Black/White achievement, especially

in the top 10% of achievement test score distribution. More

importantly, these authors note that this distribution has

not changed significantly since 1965. If the achievement gap

cannot be closed at the elementary and secondary levels, the

racially unequal social stratification is likely to become

even more pronounced. In this age of high-stakes testing,

a disproportionate number of African-American students risk

being retained or tracked into lower-level classes, thereby

becoming ineligible for college admission.

Having taught French immersion (FI) for nine years in Title

I schools with 40-99% African-American students, I had always

been impressed with my students’ academic progress in

the program. Despite, this teacher’s hunch, the true

impetus of this research was the threatened closing of all

four Louisiana FI programs in schools with over 90% African-American

students.1 This situation came about even though previous

research in the U.S. had indicated certain benefits for African-American

students in the language immersion context. For example, early

studies of partial immersion students in a large urban school

district had shown language benefits but relatively few academic

benefits in primary school (Holobow, Genesee, Lambert, Gastright,

& Met, 1987; Holobow, Genesee & Lambert, 1991). More

recently, Caldas & Boudreaux (1999) found general academic

benefits for African-American FI students in late elementary

immersion classrooms. Apart from these studies, however, little

research has been conducted on the effects French immersion

has on the academic achievement of African-American students.

This study examined differences in minority/majority student

achievement in both the French immersion (FI) and the regular

education (RE) classroom contexts. In addition, it explored

how African-American students, their peers and their teachers

(1) perceive themselves, (2) perceive others, and (3) interact

within each school setting. This article reports on the quantitative

findings alone.

Research Questions

Phase I of the study includes a quantitative analysis of covariance

comparing immersion and non-immersion fourth grade students’

LEAP (Louisiana Educational Academic Performance) scores.

Using the fourth graders’ third grade Iowa Test of Basic

skills (ITBS) scores as a control, this phase investigated:

1. Whether there were differences in academic achievement

between African-American students and White students,

2. Whether there were differences in academic achievement

between French immersion students and regular education students

and

3. Whether there was any interaction effect between these

student groups.

Participant Information

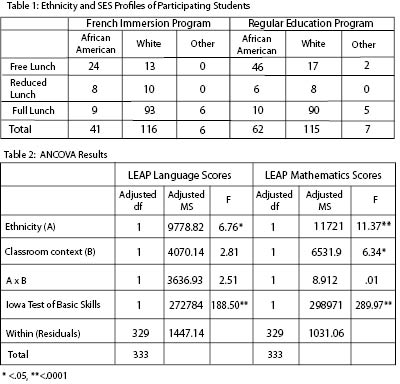

A total of 347 grade four students participated in the quantitative

phase of the study. Of these students 163 were in the FI program

and 184 were in the RE program. Table 1 summarizes information

on the socioeconomic status (SES) and the ethnicity of the

participants. While the number of students who paid full lunch

prices and the number of White students were equivalent in

both fourth grade classrooms, the RE setting had nearly thirty

more students on free lunch. More White students in both program

contexts were in the higher SES category and paid full price

for their lunches while the majority of African-American students

in both contexts were in the lower SES category (either free

or reduced lunch programs).

In terms of ethnicity, there were over twenty more African-American

students in the RE classes than in the FI classes. This was

after one FI class was excluded from the study because it

had no African-American students despite the school having

a 40% African-American student population. Students from other

ethnic backgrounds were balanced across programs.

Quantitative Results

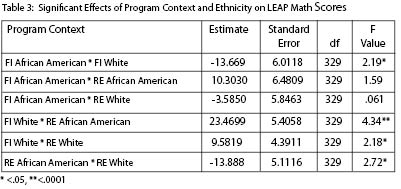

Initial findings of the quantitative data analysis revealed

(1) that White students scored significantly higher that African-American

students [see ethnicity (A)], and (2) that FI students scored

significantly higher than RE students [see classroom context

(B)]. The combined effect of ethnicity and program context

were not shown to significantly impact test performance (Table

2).

A closer examination of the subgroups found that there was

no significant difference in test scores between African-American

students regardless of program context (see Table 3 on page

10). This supports Holobow et al. (1987; 1991) earlier findings

that African-Americans in dual language programs do as well

as African-Americans in regular education. However, it must

be noted that in the area of mathematics there was also no

significant difference between the math scores of African-American

FI students and the White students in RE (although there was

a significant difference between African-American RE students

and White RE students). This may indicate a bridging of the

achievement gap, but it does not fully support Caldas and

Boudreaux (1999) who found that the achievement gap decreased

or disappeared among immersion students from diverse racial

backgrounds. This bridging of the achievement gap was found

despite the fact that one third of the African-American students

in French immersion were in a program which the qualitative

phase found to be a less than ideal immersion setting.

Suggestions for Future Research

Because of the use of the third grade Iowa Test of Basic Skills

(ITBS) scores as a covariate, the four years of immersion

schooling prior to taking the ITBS were not taken into account.

Considering that the FI students obtained ITBS scores were

higher than the RE student scores, a longitudinal study of

immersion which could account for those initial four years

would be useful. Because of the pivotal role of parents who

choose to place their children in immersion, the effect of

this parental involvement on the children’s academic

achievement also needs to be examined. The lack or absence

of African-American students in immersion programs situated

in schools with large African-American populations underscores

the need to study which students enter or leave immersion

and why. Finally, a replication of this study in a geographical

area where French is not a heritage language for the African-American

students could increase the generalizability of the findings

in this study and allow for conclusions regarding the effect

that learning a heritage language versus simply learning a

second language has on students.

Conclusion

Immersion is not a panacea for ameliorating African-American

students’ education. However, in terms of the educational

equity for African-American students, this study lends support

to earlier findings and shows that African-American students’

are as academically successful in these programs as African-American

students in non-immersion programs. Furthermore, the positive

collective self-esteem (one of the findings from the qualitative

phase of this study), extensive language skills and high LEAP

scores of the FI students in well-implemented programs indicate

that immersion is a beneficial environment for African-American

and White students.

Footnotes

1 Two of the schools were closed after this study as part

of school districts’ desegregation plans.