Getting Students to Read

The ACIE Newsletter, February 1998, Vol. 1, No. 2

By Michelle Broussard, 1st Grade Teacher, Evangeline Elementary School, Lafayette, Louisiana

Getting students to read is a formidable task. Getting students to read in the target language is even more arduous. The enormity of the task is evident when one looks at the results of Romney, Romney, and Menzies' (1995) study of French immersion students' reading habits. In this study it was found that students read French books for an average of three-and-one-half minutes per day. When compared with the amount of reading done in the students' native language-26 minutes a day-it is evident that our work is cut out for us.

The Beginning Phase

In Becoming a Nation of Readers it is suggested that children are ready to read when they have had ample experience with oral and printed language (Anderson, 1985). Immersion students in the primary grades have had little or no experience in either. In the search for techniques to encourage the students' oral language, I found an interesting article on teacher talk in the classroom (Tardif, 1994). The article suggests encouraging the students to talk and then expanding on what they say. From this idea, I started a program called "On parle en français" [We speak in French]. In this program the student would speak to me and I would then have a chance to expand upon subjects that interested the student. Students who spoke to me a number of times in French were rewarded, but I could not get the entire class to participate.

Although the students weren't participating as much as I would like, they were being exposed on a daily basis to the oral language. However, there was not much exposure to the printed language. To remedy this situation I looked to a technique supported by the research of Romney, Romney, and Braun (1988) on the positive effects of reading aloud in the primary classroom. They recommend reading aloud to the students every day in order to help students develop their receptive vocabulary, their free recall, and their ability to make themselves understood. Because my students were non-readers, I started a morning story time to expose them to more printed language.

|

her French reading skills.

Run-down equipment: A blessing in disguise

Over the past three years of teaching immersion, these two techniques-"On parle en français" and daily story time-were my primary improvements until the happy day when my outdated tape player quit working right during the middle of center time. Since I was already occupied with a small group of students, I simply told the students at the listening center to look at the book and then do the coloring assignment that went with it. Out of the blue, one of the students asked me if she could try to read the book to her group. That hadn't occurred to me, since it was only the second month of first grade and the students had yet to learn how to read in their first language, much less in the target language. To my surprise she read the book nearly flawlessly. (It was a very repetitive book and she had memorized the words.) The next morning the child asked if she could read the book to the class during our morning reading time.

Since then, I haven't looked back.

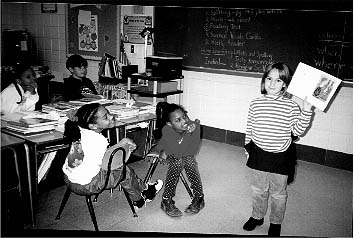

I received an avalanche of requests from the students who wanted to read their books to the class. I started writing notes home to parents telling them that their child had read a book in class. I went through all my Post-It notes before I had the idea of printing up labels on my computer that I could stick on the students themselves. I had so many requests that I enlisted the help of the English-program teachers. Reading to the English-program classes in the school was incorporated into my center time rotation. Two groups of students per day left class during center time to read their French books to the regular education classes.

I noticed that some students kept reading the same books over and over again while others would experiment and try to read the more difficult books. I decided we needed a system to keep track of the books read by the students. The books that they read are numbered, so it was easy to create a wall chart on which the students check which books they have and have not read. Any books that are not in the series are just added as an extra title to the wall chart.

Je lis chez moi (I read at home)

We were doing so much to encourage the students to read that I was beaming with pride for the second six-weeks' parent/teacher meeting. While explaining to one of my parents how the system worked, her child volunteered to read a book to her. When tears started to well up in the parent's eyes, I realized that an important component was missing from the program. I started sending the books home with the students to read to their parents. I also sent home harder books with cassettes in order to expose the students to even more written and oral language.

Conclusion

Since I have started the reading program, it is amazing how the students' oral language skills have improved. It is hard to give empirical evidence for the students' improvement, but after having taught first grade French immersion for three years, I can honestly say that I have never had as many children speaking at this high a level.

I will say that, in reference to the "On parle en français" program, there has been a dramatic change in the criteria needed to check the chart. At the beginning of the school year the students would check on a wall chart if they said a word or two in French. Now the student can check only if they speak using entire phrases.

What can I say? They are doing wonderfully and they are always eager to read. I'm hoping that once they get used to reading on their own in French that they will continue to do so. I want my students to read more than a paltry three-and-a-half minutes a day!